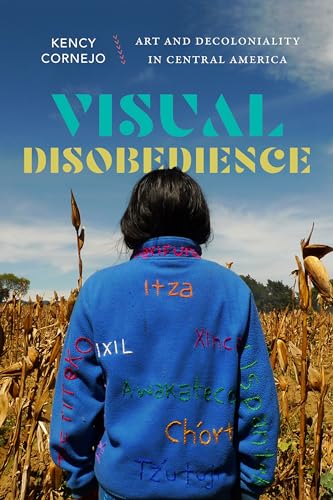

Visual Disobedience: Art and Decoloniality in Central America

Kency Cornejo

Publisher

Duke University Press Books

Publication Date

10/18/2024

ISBN

9781478030546

Pages

304

Categories

Questions & Answers

Central American artists engage in "visual disobedience" by challenging colonial legacies and visual coloniality through various creative and critical practices. They use performance art, video, installation, and object-based works to disrupt the erasure of Indigenous history and experiences. By incorporating Indigenous epistemologies and cosmologies, they reinsert and reinscribe their own perspectives, thereby decolonizing art and knowledge. Artists also focus on issues like femicide, displacement, and criminalization, using their bodies and spaces to create counternarratives that defy the dominant, colonial narratives. Their work often centers on sensory experiences, emphasizing the importance of memory, healing, and community. Through these acts, they resist visual erasure, thingification, and extractivism, contributing to a broader movement for decolonization and justice.

The role of aesthetics in colonialism is deeply intertwined with domination and erasure. Aesthetics, as a Western concept, was historically used to define and control the perception of the world, often centering European men's senses and subjectivity. This led to the devaluation of non-Western cultures and the portrayal of colonized peoples as subjects of art rather than producers or receptors of art. Central American artists decolonize this concept by redefining aesthetics from the perspective of those who have been marginalized and erased. They use their art to challenge colonial narratives, reclaim their identities, and assert their existence. This involves embodying resistance, using their own bodies and spaces for interventions, and creating counter-narratives that defy the erasure and dehumanization imposed by colonial aesthetics. By doing so, they contribute to a decolonial aesthetics that is rooted in the experiences and perspectives of those who have been historically oppressed.

The artists in the book address issues like Indigenous genocide, gender-based violence, displacement, and criminalization through various forms of visual disobedience. They use performance, conceptual art, installations, and video to:

-

Indigenous Genocide: Maya artists like Chavajay, Pichillá, and Monterroso bring Indigenous spirituality, gender, and earth relations to the forefront, connecting current repression to the Spanish conquest and colonial legacies.

-

Gender-Based Violence: Artists like Elyla (Fredman Barahona) and others use their bodies to challenge gender norms and highlight the violence faced by women and non-binary individuals in patriarchal societies.

-

Displacement and Migration: Through "shifting the border," artists like Habacuc and del Cid create counternarratives that focus on the complexities of migration, including family separation and the systemic violence that drives people from their homes.

-

Criminalization: Artists like Zavaleta and Siu expose the criminalization of marginalized groups, including Indigenous peoples and Black individuals, through visual thingification and the carceral logic of colonialism.

These artists' works collectively challenge the dominant narratives and expose the ongoing impacts of colonialism and its legacies in Central America.

The concept of "visual coloniality" is crucial in understanding the impact of colonialism on Central American art and society. It refers to the ways in which colonial powers have used visual means to dominate, erase, and exploit colonized peoples. This manifests in several ways:

-

Visual Erasure: Colonial powers have systematically deleted Indigenous artistic history and significance, imposing their own standards as superior. This rewriting of visual history serves imperial interests.

-

Visual Thingification: Indigenous and enslaved African peoples were dehumanized and criminalized through visual fabrications, justifying violence and disposability. This dehumanization is a tool for colonial domination.

-

Visual Extractivism: Indigenous designs and visual knowledge have been stolen and exploited for profit, perpetuating power imbalances and violence.

In Central American art, artists engage in "visual disobedience" to counter these mechanisms. They use their work to expose ongoing colonialism, defy visual coloniality, and reveal the radicalness of their art and visions. This includes reinserting Indigenous epistemologies, critiquing Western beauty standards, and addressing issues like displacement, violence, and criminalization. Visual disobedience is a powerful tool for challenging the legacy of colonialism and promoting a more just and inclusive society.

The book "Visual Disobedience" contributes significantly to the discourse on migration and decolonization by focusing on Central American art as a means of resistance against colonial legacies and systemic violence. It highlights the role of artists in challenging visual coloniality and creating counternarratives that reveal the complex realities of migration, displacement, and the ongoing impact of colonialism.

The implications of its findings for understanding Central American art and culture are profound. The book emphasizes the importance of recognizing the agency and creativity of Central American artists in shaping their own narratives, which often go against the dominant, Eurocentric narratives. It underscores the significance of decolonial aesthetics in reimagining and redefining Central American identity and culture, emphasizing the interconnectedness of race, gender, and coloniality in shaping the region's history and contemporary experiences. This perspective challenges the exclusion of Central American art from mainstream narratives and highlights the need for a more inclusive and diverse understanding of art and culture.