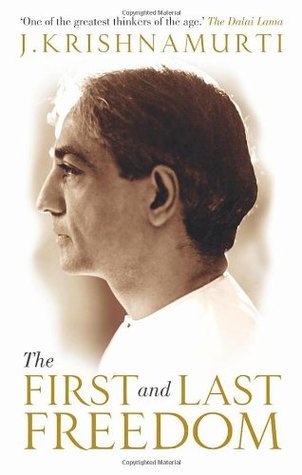

The First and Last Freedom

J. Krishnamurti

Publisher

Rider & Co

Publication Date

8/1/2013

ISBN

9781846043758

Pages

352

Categories

About the Author

J. Krishnamurti

Questions & Answers

J. Krishnamurti argues that self-knowledge is crucial for solving human problems and achieving freedom by emphasizing the individual's role in creating the world's issues. He believes that the individual, rather than external forces or institutions, is responsible for the problems of suffering, conflict, and misunderstanding. Krishnamurti asserts that understanding oneself is the first step in transforming one's thoughts, actions, and relationships. By becoming aware of one's thoughts, feelings, and reactions, one can recognize and change the patterns of behavior that contribute to societal issues. He emphasizes the importance of self-awareness, which leads to clarity, freedom from beliefs, and the ability to act without contradiction. Krishnamurti suggests that self-knowledge is an ongoing process of inquiry and understanding, which ultimately leads to a state of peace, creativity, and freedom from the constraints of the mind.

The mind plays a significant role in creating suffering through its tendency to cling to beliefs, knowledge, and desires. It creates a sense of self through these constructs, leading to conflict, isolation, and a lack of peace. To transform the mind and achieve a state of peace and clarity, one must become aware of these patterns. This involves observing thoughts and emotions without judgment or identification, allowing them to pass without causing lasting impact. By understanding the nature of the mind and its processes, one can free oneself from the cycle of suffering. This transformation requires a commitment to self-awareness, self-inquiry, and the cultivation of a quiet, still mind. Through this process, the mind can become a vessel for clarity and insight, leading to a state of peace that transcends the temporary nature of the mind's fluctuations.

Krishnamurti critiques organized religion, nationalism, and other systems of belief by arguing that they are based on separation and division, rather than unity and understanding. He believes that organized religions, with their dogmas and rituals, create a false sense of security and lead to conflict and division among people. Nationalism, he claims, is a form of isolation and power-seeking that hinders peace and global unity.

He proposes alternatives such as self-knowledge, awareness, and a choiceless awareness of the present moment. Krishnamurti emphasizes the importance of understanding oneself and one's thoughts, feelings, and actions, rather than relying on external authorities or systems. He suggests that by observing and understanding the workings of the mind, one can achieve a state of creative emptiness, where newness and transformation can occur. This process of self-awareness leads to a deeper understanding of relationships, love, and the nature of reality, ultimately leading to a more peaceful and harmonious world.

The relationship between action and thought is deeply intertwined. Typically, action is guided by thought, which is shaped by past experiences, beliefs, and preconceived ideas. This creates a cycle where thought influences action, and action reinforces thought, often leading to repetitive patterns and limitations.

To achieve action without being limited by preconceived ideas, one must become aware of the thought process and its influence on action. This involves observing thoughts without judgment or identification, allowing them to arise and pass without attachment. By doing so, one can recognize when an action is being driven by an idea or memory rather than by the present moment.

This awareness leads to a state where action is spontaneous and arises naturally from the current situation, without the need for an external idea to guide it. This kind of action is not limited by past conditioning and can be more creative and effective. It requires a deep understanding of oneself, constant awareness, and the ability to let go of preconceived notions, allowing for a more fluid and open-minded approach to life.

J. Krishnamurti defines truth and reality as the eternal, timeless, and immeasurable aspects of existence that transcend the limitations of the mind and its constructs. He emphasizes that truth is not a concept to be believed or a goal to be achieved but an experience that arises when the mind is free from desire, knowledge, and belief. Reality, according to Krishnamurti, is not something to be sought outside oneself but is present in the immediate moment, in what is.

The role of the individual in discovering truth and reality is to engage in self-awareness and introspection. This process involves understanding the workings of the mind, including its conditioning, desires, and the tendency to seek security through beliefs and dogmas. By observing the mind's processes without judgment or resistance, one can gradually free the mind from its limitations and allow truth and reality to emerge. This requires a state of 'choiceless awareness,' where the individual is fully present and attentive to the moment, enabling direct perception and understanding of the true nature of reality.