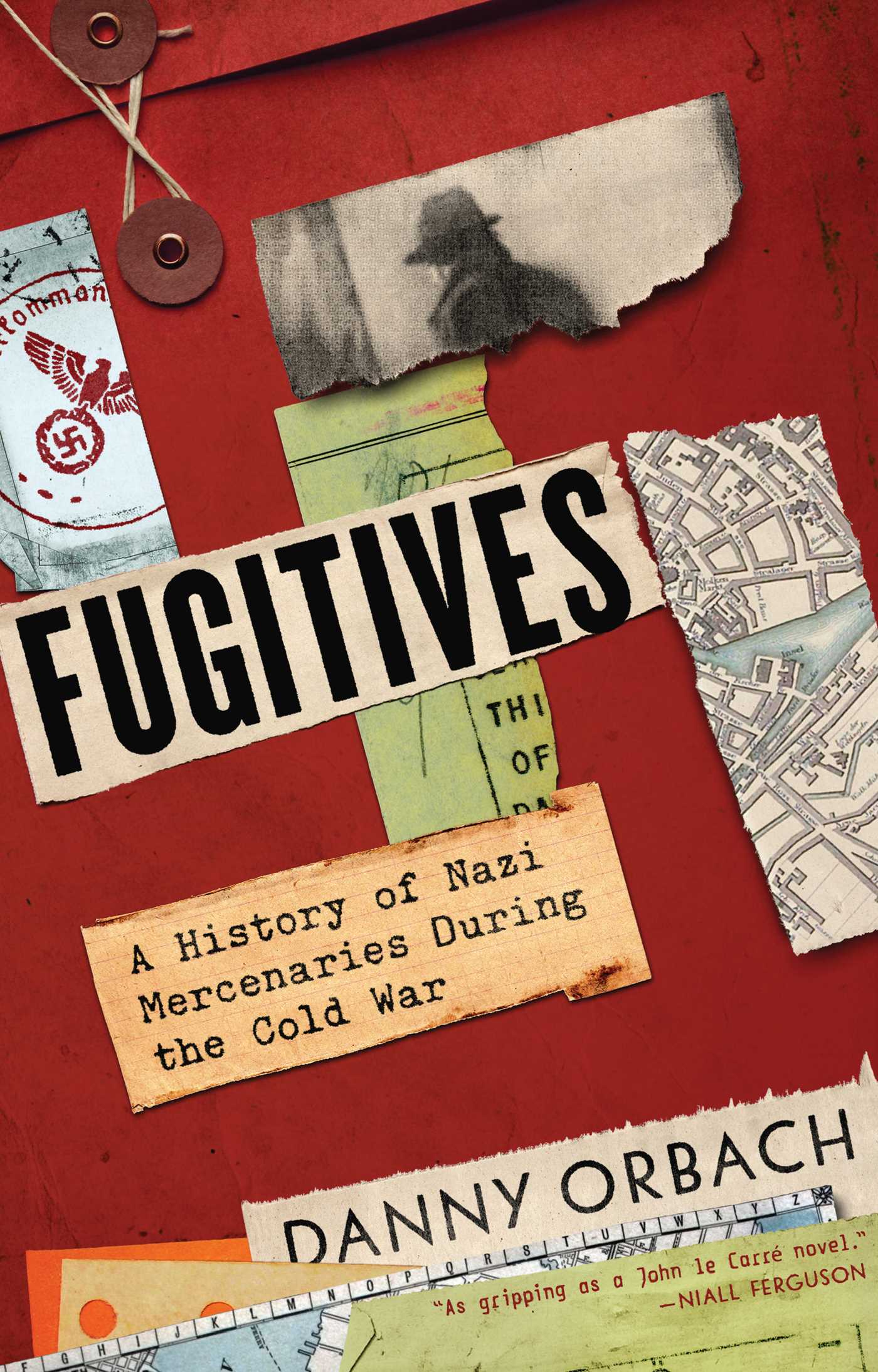

Fugitives: A History of Nazi Mercenaries During the Cold War

About the Author

Questions & Answers

The legacy of Nazi Germany and its former agents significantly influenced the geopolitical landscape of the Cold War, particularly through intelligence operations and proxy conflicts. Nazi war criminals and ex-intelligence officials, such as Reinhard Gehlen, were often employed by Western and Eastern powers due to their expertise and anti-communist sentiments. This practice, however, led to moral compromises and security risks, as these individuals could be susceptible to Soviet manipulation.

In the Middle East, Nazi arms dealers and mercenaries, like Ernst-Wilhelm Springer and Alois Brunner, were involved in clandestine arms trafficking, which fueled proxy conflicts like the Algerian War of Independence. This not only undermined Western interests but also exacerbated tensions between France and West Germany.

Moreover, the presence of Nazi fugitives in the Middle East and their involvement in intelligence operations led to exaggerated fears and overreactions, as seen in Israel's response to the German rocket scientists in Egypt. These events, driven by the power of the "Nazi" label, often led to irrational policies and covert operations that sometimes backfired, as in the case of the Mossad's Operation Damocles against the German scientists.

In summary, the legacy of Nazi Germany and its former agents influenced the Cold War by complicating intelligence operations, fueling proxy conflicts, and leading to overreactions based on moral and political considerations.

Following the fall of the Third Reich, former Nazis employed various coping and adjustment strategies:

-

Anti-Communism: Many chose to align with the West, embracing Western democracy and anti-communism. This allowed them to integrate into post-war societies while maintaining a semblance of their former beliefs.

-

Pro-Soviet Alignment: Some, particularly those with an aversion to Western democracy, aligned with the Soviet Union, using their anti-Western stance to their advantage.

-

Neutralism: Others, like 'neutralists,' sought to play all Cold War actors against each other for personal gain, without committing to any ideology.

-

Freelance Mercenaries: Some became freelance arms traffickers, spies, and covert operators, focusing on financial compensation rather than ideology.

-

Nazi Revanchists: A few retained fantasies of a future National Socialist resurgence, often engaging in clandestine activities to achieve this goal.

These strategies shaped their involvement in post-war intelligence and covert activities. They often became double or triple agents, exploiting their past for personal gain and ideological reasons. Their presence in intelligence agencies and covert operations blurred the lines between pro-Western, pro-Soviet, and Nazi revanchist factions, leading to complex and often dangerous situations. Their moral compromises and shifting allegiances significantly influenced the course of the Cold War, the history of Germany, and regional conflicts.

The illusion of control and self-deceit among former Nazis and their Western and Soviet allies significantly contributed to the complexities and dangers of the Cold War intelligence landscape. Former Nazis, like Reinhard Gehlen, often exaggerated the communist threat, leading Western allies to employ them despite their Nazi pasts. This reliance on former Nazis, who were often unreliable and had their own agendas, led to intelligence failures and compromised operations. For instance, Gehlen's organization, the Gehlen Org, was infiltrated by Soviet agents, undermining Western intelligence efforts.

Similarly, the Soviet Union exploited the West's need for intelligence on the Soviet bloc by recruiting former Nazis and other war criminals. These individuals, like Heinz Felfe, provided valuable information to the Soviets, but their presence also led to espionage scandals and damaged the credibility of Western intelligence agencies.

Moreover, the exaggerated fear of Nazis and their influence, as seen in the Israeli response to the presence of German scientists in Egypt, led to irrational policies and covert operations that sometimes exacerbated tensions and risks. The illusions of control and self-deceit among all parties involved in the Cold War intelligence landscape thus created a volatile and dangerous environment.

During the Cold War, intelligence agencies often found themselves at odds with national policy, particularly when covert operations diverged from stated goals. Initially, agencies like the Gehlen Org in West Germany and the SDECE in France were established to counter Soviet influence and communism. However, their reliance on former Nazis and arms trafficking, as well as their involvement in Middle Eastern conflicts, often contradicted their governments' official policies. For instance, the BND's arms deals with the FLN in Algeria threatened West Germany's relationship with France and its commitment to Western Europe. Similarly, Israel's overreaction to the presence of German scientists in Egypt, including the Mossad's Operation Damocles, led to a crisis in its relationship with West Germany and the U.S. These examples illustrate how covert operations, driven by the desire for immediate gains or to counter perceived threats, sometimes overshadowed long-term national interests, leading to policy inconsistencies and international tensions.

The collaboration between Western intelligence agencies and former Nazis had significant long-term consequences. Firstly, it compromised the effectiveness of Western intelligence services, as many of these former Nazis were double agents or spies for the Soviet Union. This was particularly damaging for West Germany's intelligence capabilities against the Eastern Bloc and the Soviet Union. Secondly, the use of former Nazis as intelligence assets fueled anti-communist sentiments and the "Red Scare," which led to exaggerated fears of communist infiltration and contributed to the escalation of the Cold War. This collaboration also impacted historical narratives by complicating the moral and ethical dimensions of the post-war period. It blurred the lines between allies and enemies, and the legacy of Nazi war criminals was often overlooked or downplayed. Additionally, the collaboration contributed to the normalization of the use of extreme measures in intelligence operations, which had lasting effects on the conduct of espionage and covert actions during and after the Cold War.